Updated March 1, 2024. Original publication date April 1, 2023

Have you found yourself in need of a new physician? You relocated. Your physician retired. You need a specialist. Your current practitioner (or their office staff) no longer meets your needs. Whatever the reason, the search for a new practitioner is not as simple as it once was. In years past, you surveyed family and friends, sought advice from other practitioners, and very importantly, checked with your insurance company. Today however, thanks to the pervasive reach of the internet, there are a myriad of additional resources at one’s disposal: Yelp, Healthgrades, Vitals, Zocdoc, and Ratemds to name a few. As a result, you may think the search for respected and qualified practitioners has become easier. Sadly, you would be mistaken.

Increasing Appointment Wait Times

Whether you need to schedule a sick visit, specialist visit, or annual physical exam, a potentially lengthy waiting period for an appointment is very likely in your future. A poll of family and friends finds that a sick visit can take up to 2 weeks. A specialist visit has a conservative 1-1/2 month delay, while an annual exam takes careful planning and forethought to secure an appointment roughly 3-6 months in the future. Heaven forbid your practitioner falls ill, goes on vacation, or simply elects to take some personal time. Where is one to turn? You may try to make an appointment with the on-call or “covering” doctor. Your success will likely depend on your ability to actually speak with the covering practitioner’s office staff, or your willingness to wait 2-4 hours for a same-day walk-in appointment (if even permitted).

Why these delays? The answer is likely related to a complex set of factors: 1.) Increased patient demand, thanks in some part to the Affordable Care Act, 2.) An aging American population requiring more specialized care, 3.) An aging physician population, 3.) Stagnant growth in the surgical specialties, and 4.) A convoluted insurance physician reimbursement process. While many of these factors are addressed in the American Association of Medical Colleges’ “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034,” one that is conspicuously overlooked is the upsurge in concierge medicine, and to some extent, the recent proliferation of direct primary care practices (DPC’s).

Concierge Medicine

What is concierge medicine? This refers to membership-based (fee-based) medical practices. Members pay their practitioner, or medical practice, a fee which ranges on average from $1500-$5000/per person per year. Expect higher fees in more affluent areas. This fee, generally billed monthly or yearly, serves as a retainer; reminiscent of businesses and wealthy individuals who have attorneys on retainer, and therefore do not pay hourly fees for services. Subsequently, should you need to see your concierge practitioner, you can do so without delay. More importantly, the expectation is that you will receive individualized, unrushed, attentive care. As an added benefit, many concierge practices offer multi-specialty services with expedited referrals. The goal is to optimize each member’s health by prioritizing patient care and enhancing the relationship between practitioner and patient. Membership-based practitioners purport to be able to provide such services, as the annual fees afford them the flexibility to dedicate quality time to each member, by limiting their practices to a smaller number of patients. The perk: 24/7 practitioner access, 365 days/year, including emergency treatment and house calls. Larger concierge practices frequently offer functional and integrative medicine, and holistic care (IV vitamins, allergy testing, acupuncture, chiropractic treatment, ayurvedic medicine, naturopathic nutrition, etc.). Individuals desiring immediate practitioner access, and those with chronic conditions requiring ongoing evaluation and care, reportedly most appreciate concierge medicine.

Direct Primary Care (DPC) Medicine

A similar, albeit different healthcare delivery model from concierge medicine, is direct primary care (DPC). Like concierge medicine practices, direct primary care practices are available 24/7, 365 days/year. While DPCs also charge their members a membership fee (average $65-125/month for adults), with older adults (65+) paying higher rates, the fee is generally less than that of concierge medical practices. Membership fees are typically billed monthly or annually. In addition, some DPCs also charge per-visit fees and additional flat rate fees for select treatments or procedures. Note however, that while any additional patient-practitioner per-visit fee may not exceed one’s monthly membership fee, the same does not apply to add-on services (laboratory, radiology, etc.). Membership fees typically cover routine primary care services (sick visits, medication review and follow-ups, annual physical exams including basic laboratory tests, etc.). Advanced laboratory tests, radiology and other diagnostics (such as electrocardiograms) may be subject to ancillary fees. Specialist visits, complex urgent care, hospitalization, advanced diagnostic testing (MRI, PET scan, etc.) and prescription drugs are services not commonly covered by a DPC membership fee. Therefore, those opting to join a DPC are encouraged to maintain a traditional healthcare plan. High deductible, catastrophic plans are recommended for those with a more limited budget.

Differences Between Concierge Medicine and Direct Patient Care

While both concierge medicine and direct primary care provide members 24/7, 365-day access to practitioners, there are several fundamental differences between the two. Concierge medical practices tend to provide more comprehensive services, expedited access to specialists, and practitioners who coordinate members’ overall healthcare among all specialists, hospitals and rehabilitative care. Those old enough to remember non-membership-based physician house calls and visits in the hospital by their primary care practitioner may really appreciate concierge medical practitioners. Due to the greater number of services and care coordination generally provided by concierge medical practices, their membership fees are typically higher than DPC fees.

Not surprisingly, one very important difference between concierge medicine and DPC is financial in nature. Many concierge medical practices accept private healthcare insurance and/or Medicare, whereas DPC practices do not. This distinction is very important, as healthcare practitioners that accept private or governmental insurance are required to comply with various federal and state mandates. Since DPC providers do not accept insurance, the degree of compliance with various state regulations has garnered increased attention. As of 2020, the vast majority of states “define DPC as a medical service outside of state insurance regulation.” As a result, like concierge medicine, DPC needs to be combined with, at minimum, a HDHP in order to avoid incurring a state-mandated fee for opting out of a traditional healthcare plan.

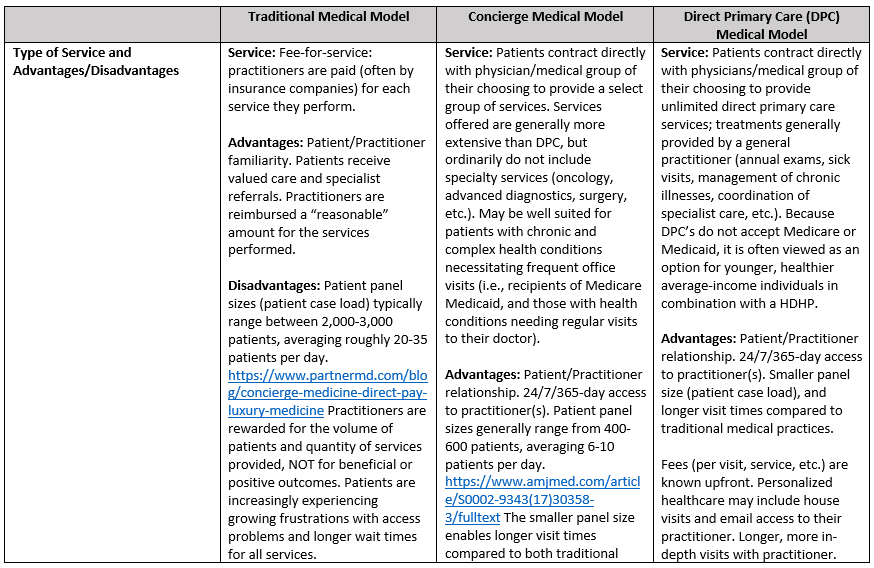

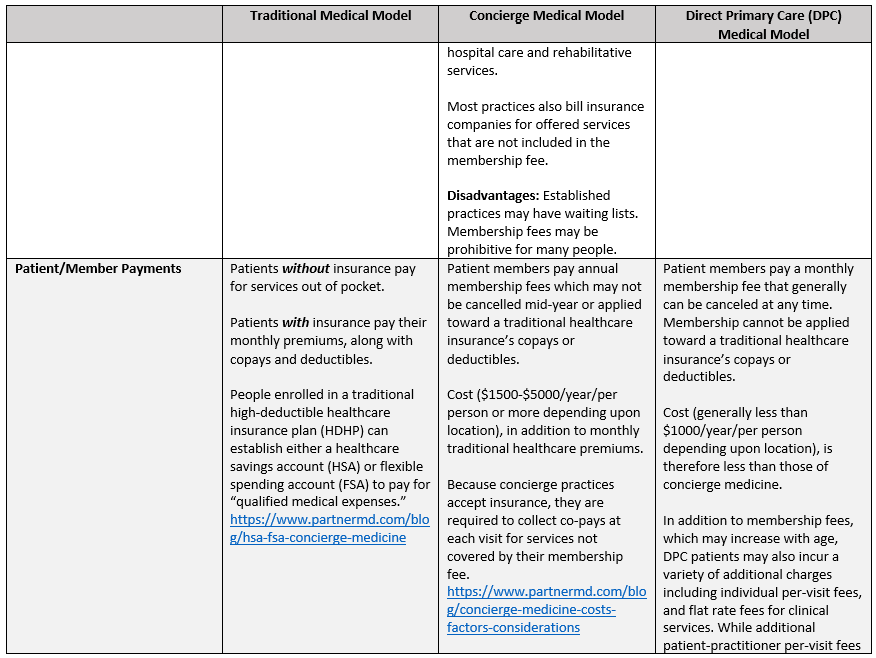

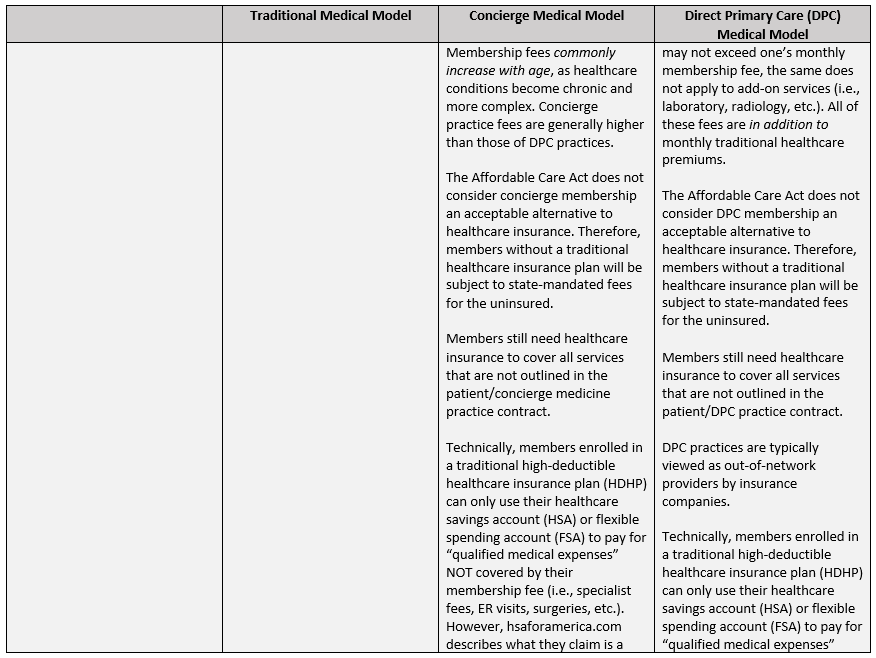

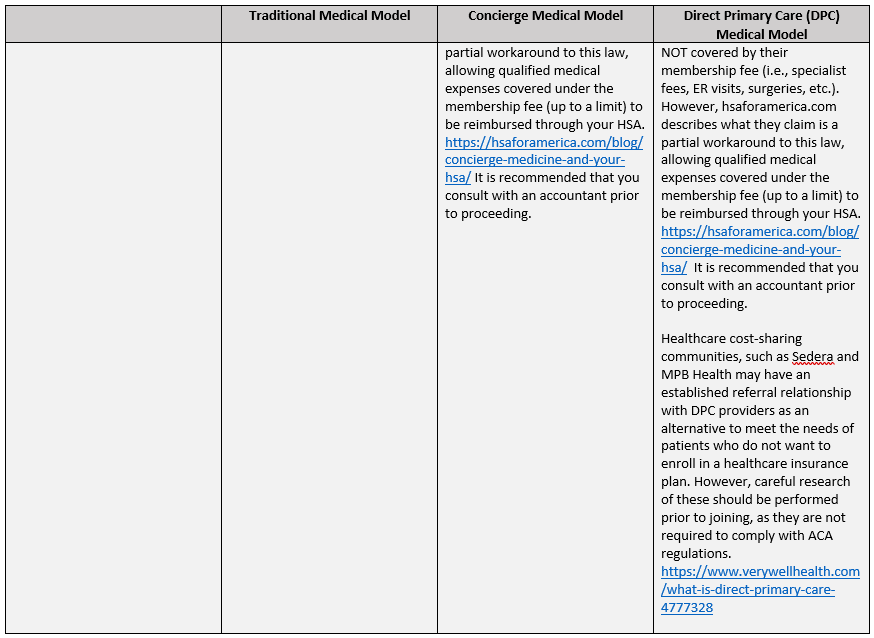

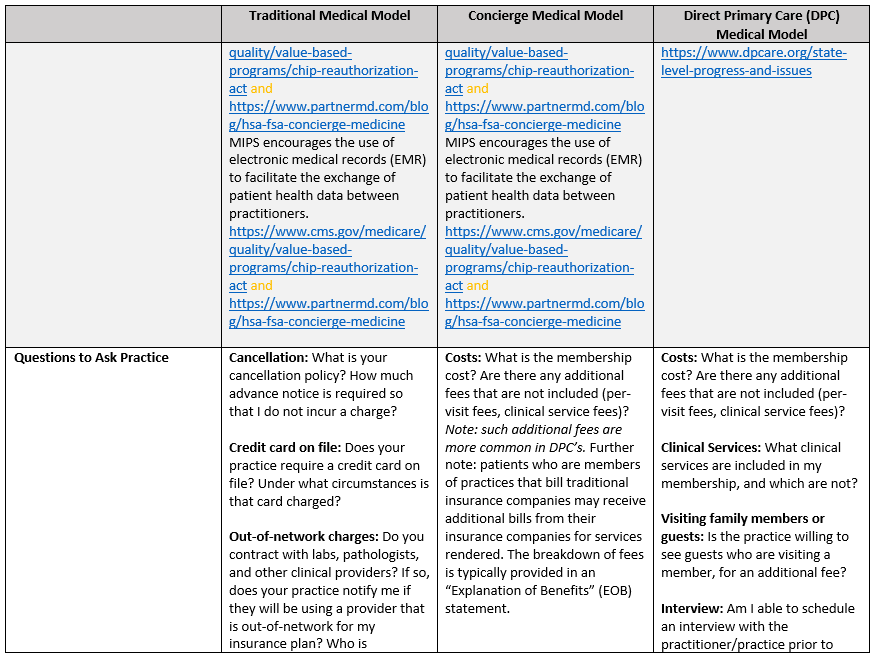

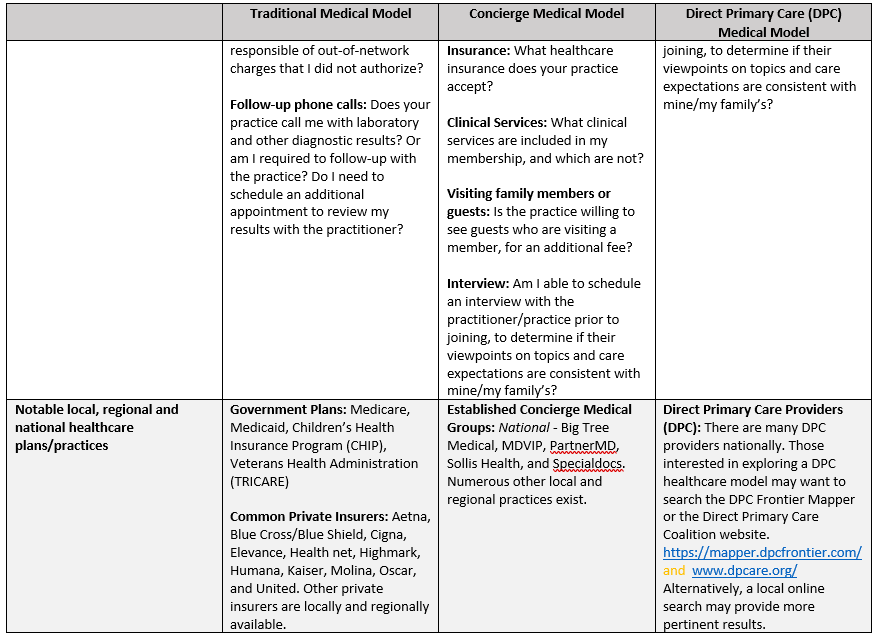

Therefore, it is advised that both concierge and DPC members maintain a traditional healthcare plan to cover essential services not provided by their respective membership plans, such as emergencies (heart attack, stroke, etc.), complex illnesses (cancer, diabetes, degenerative diseases, etc.), and catastrophic injuries (major accidents, etc.), as well as to be in compliance with Affordable Care Act regulations. (See the below table for a more detailed description of the differences between traditional, concierge and DPC healthcare delivery models.)

The Desire for Alternatives to Traditional Patient Healthcare Service

Why do people consider paying hundreds to thousands of dollars per year, in addition to health insurance premiums, just to see a specific practitioner? Is this not yet another example of services catering to the wealthy, that are out of reach for the average American? Didn’t physicians take an oath (Hippocratic) to care for all patients, regardless of their financial status? The answer to the first question is that people of all income levels are tired of waiting weeks to months to see their regular practitioner. They don’t want to have to resort to visits to urgent care or the emergency room, where costs are higher and they have no relationship with the attending practitioner. They want someone who will take the time to listen to what is ailing them, answer their questions, and not leave them with the perception that they were just rushed through an assembly line of care. As to the second question, yes, in all likelihood many wealthy families comprise a large percentage of the clientele at concierge medical practices. After all, it is a fee on top of, not a replacement for, medical insurance. However, there appears to be a growing number of middle-class families that are opting in to either direct patient care (DPC’s) or concierge medicine practices, for the aforementioned reasons. Some may elect to prioritize their ability to see a healthcare practitioner over vacations and other nonessential items. Others, already struggling to pay healthcare premiums, will simply be unable to afford the added service. As for the final question, yes, physicians did take an oath to care for all patients. However, they did not take an oath to be paupers. Many have medical school loans to pay off, families to support, and some even desire a reasonable work-life balance. However, more and more physicians who have been practicing for several decades have grown increasingly dismayed by the changes in the healthcare system. They no longer see the value in the fee-for-service model that encourages patient volume over quality. Many agree with their patients who feel office visits are rushed. They desire smaller patient-loads, where they can have more in-depth visits with their patients, all of which are reportedly discouraged in the traditional fee-for-service healthcare delivery model.

Are Concierge and DPC Healthcare Delivery Models Worth it?

Are these alternative healthcare delivery models worth it? That depends on a variety of considerations, not the least of which is one’s perception of the accessibility and quality of care generally available in their community. This takes me full circle to what led to the writing of this article. At the outset of each new year, I schedule my family members’ annual physical exams. Despite the years-long relationship we each have with our respective practitioners, such exams generally require a minimum of 4 months advance planning. In the last few years, I’ve allocated closer to 6 months, as reserving a spot for the roughly hour-long exams has necessitated the additional lead time. This year, the scheduling process did not go as planned when we were abruptly informed that our primary care internist, in his early 70’s, was taking a four month leave of absence, although not retiring. A referral to another practitioner was given to provide coverage in the interim, but repeated attempts to contact him went unanswered. It begged the question: how much further off would our practitioner’s retirement be? The day would come eventually, and we wanted any switch to be on our terms, not forced upon us. Thus, we decided it was probably time to start looking for a new internist altogether. I spent approximately twenty hours going through the steps outlined at the beginning of this piece. I diligently researched and jotted down the names of practitioners that were highly recommended, and confirmed that they were in-network for my healthcare plan. Then, one-by-one I visited the websites of those who had one available, or called the practices directly. To my astonishment, the vast majority of my selections were all part of concierge medicine, some having just migrated to the model earlier this year. Honestly? What stupefied me even more was that a few already had waiting lists for new patients, some 2+ years out.

Decisions: To Join or Not Join a Membership-Based Practice. What Makes a Quality Physician?

My significant other and I had a discussion regarding the best course of action. We elected to refrain from joining a fee-based practice at this time, in favor of re-evaluating our “search” criteria. Our long-time internist had a dedicated patient following. Patients waited for hours in the waiting room, and some drove long distances, just to see him. He saw multiple generations from the same family, taking the time to listen, really listen, to patients concerns and fears. He had the rare but prized ability to appear calm in even the most trying situations. He was concierge medicine without the price tag (notwithstanding the hours long wait for walk-in appointments). We acquiesced and decided that the following criteria would no longer be a factor in our search: 1.) Rude office staff – After all, according to online practitioner ratings, the vast majority of today’s office personnel lack cordial communication skills. 2.) Condescending practitioners – While our current practitioner is in no way condescending, we have been around the block, and have experienced our share of condescending ones in the past. We decided that excellence in one’s specialty must take priority over bedside manner. 3.) Long wait times – as previously noted, given the high demand for our long-time practitioner, we were already accustomed to taking an entire morning, or afternoon, off when we had visited him.

Our revised physician search criteria resulted in roughly a half-dozen “quality” practitioners. We are hoping to secure an appointment with one of them in the relatively near future. Our hope is that whomever we end up with, they are at least 80% of the physician our current practitioner is, and that their waitlist for new patients is less than 6 months. To those who, like my family, find themselves in the search for a new healthcare provider, I hope this article provides some helpful guidance and insight into the bewildering array of internet search websites and alternative healthcare delivery models.

Update

Sadly, we subsequently learned that our beloved practitioner decided to retire. After experiencing an avoidable adverse event thanks to my first referred physician dismissing a medical concern of mine, a well-respected urgent care physician handed me a sheet with a few dozen practitioners listed on it. He circled one. He said, “She is very good. She will listen to you. Tell her I sent you.” We now have a new internist! She does not have terribly long wait times (so far), is not condescending, takes the time to listen, and importantly, remembers our medical history.

The below table provides a succinct overview of the similarities and differences between traditional, concierge and direct primary care healthcare delivery models.

Note: Links referenced in the table are provided in the reference section after the table

*HDHP: The IRS defines High-deductible healthcare insurance plans (2024) as those with annual deductibles of $1600 or more for individuals, and $3200 or more for families. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-23-23.pdf and https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidrae/2023/12/07/what-are-the-new-2024-health-savings-accounts-hsa-limits/

**HSAs and FSAs allow participants to set aside pre-tax earnings for “qualified medical expenses.” HSA contribution limits for 2024 are: $4150 for individuals and $8300 for families. Individuals 55 and over are permitted to contribute an additional $1000. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidrae/2023/12/07/what-are-the-new-2024-health-savings-accounts-hsa-limits/

References

Beverly Hills Concierge Doctor, Beverly Hills Concierge Doctor, beverlyhillsconciergedoctor.com/.

“The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034.” Association of American Medical Colleges, IHS Markit Ltd., June 2021, https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?tlaAppCB.

“Concierge Care.” Concierge Medicine Coverage, U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/concierge-care.

Dalen, James E., and Joseph S. Alpert. “Concierge Medicine is Here and Growing!!” The American Journal of Medicine, vol. 130, no. 8, Aug. 2017, pp. 880–881, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.031

“Direct Primary Care: Evaluating a New Model of Delivery and Financing.” Society of Actuaries, Society of Actuaries, May 2020, http://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/files/resources/research-report/2020/direct-primary-care-eval-model.pdf.

Eskew, Phil. “DPC Frontier Mapper.” DPC Frontier, DPC Frontier, mapper.dpcfrontier.com/.

Freedman, Max. “What Are MACRA and MIPS?” Business News Daily, Business News Daily, 23 Oct. 2023, http://www.businessnewsdaily.com/16581-macra-mips.html.

“Frequently Asked Questions.” DPC Nation, DPC Nation, dpcnation.org/faq/.

Gifford, Melissa. “Concierge Medicine vs. Direct Pay Primary Care vs. VIP Medicine.” partnerMD, partnerMD, 20 June 2023, http://www.partnermd.com/blog/concierge-medicine-direct-pay-luxury-medicine.

Hunt, Janet. “Direct Primary Care Alternatives to Health Insurance.” The Balance, The Balance, 21 Oct. 2021, https://www.thebalancemoney.com/direct-primary-care-alternatives-for-health-insurance-4164823.

Ito, Robert. “L.A.’s Concierge Medical Services Woos VIPS with Plush Amenities — but Not Everyone Thinks That’s Healthy.” Los Angeles Magazine, Los Angeles Magazine, 1 Apr. 2021, lamag.com/featured/concierge-medicine-los-angeles.

Kiss, Janet. “The Pros and Cons of Concierge Medicine for Patients.” PartnerMD, PartnerMD, 1 Feb. 2023, https://www.partnermd.com/blog/concierge-medicine-patients-pros-cons.

Kona, Maanasa, et al. “Direct Primary Care Arrangements Raise Questions for State Insurance Regulators.” The Commonwealth Fund, The Commonwealth Fund, 22 Oct. 2018, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/direct-primary-care-arrangements-state-insurance.

Lasher, Joe. “How to Use Your HSA or FSA for Concierge Medicine.” PartnerMD, PartnerMD, 17 Apr. 2023, http://www.partnermd.com/blog/hsa-fsa-concierge-medicine.

Long, Wiley. “Concierge Medicine and Your HSA.” HSA for America, HSA for America, 21 July 2020, hsaforamerica.com/blog/concierge-medicine-and-your-hsa/.

“Macra: MIPS & Apms.” CMS, U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.

Norris, Louise. “How Does Direct Primary Care Work?” Verywell Health, Verywell Health, 1 Sept. 2023, http://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-direct-primary-care-4777328

Rae, David. “The New 2024 Health Savings Accounts (HSA) Limits Explained.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 7 Dec. 2023, http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidrae/2023/12/07/what-are-the-new-2024-health-savings-accounts-hsa-limits/.

“Rev. Proc. 2023-23.” IRS.Gov, IRS.gov, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-23-23.pdf.

Robinson-Walker, Dawnielle. “What Is Concierge Medicine and Is It Worth the Price Tag?” Edited by Alena Hall, Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 8 Nov. 2022, https://www.forbes.com/health/healthy-aging/concierge-medicine/#:~:text=Concierge%20care%20is%20not%20an,health%20plan%20to%20save%20money.

Rosenberg, Alex. “What Is Direct Primary Care, and How Much Does It Cost?” MarketWatch, MarketWatch, 27 Apr. 2023, http://www.marketwatch.com/story/what-is-direct-primary-care-and-how-much-does-it-cost-125df60.

Smith, Zack. “Concierge Medicine: Costs, Factors, and Considerations.” PartnerMD, PartnerMD, 27 Apr. 2023, http://www.partnermd.com/blog/concierge-medicine-costs-factors-considerations.

“State Policy.” Direct Primary Care Coalition, Direct Primary Care Coalition, http://www.dpcare.org/state-level-progress-and-issues.

U.S. Concierge Medicine Market Size & Trends Report, 2030, Grand View Research, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-concierge-medicine-market-report.

“U.S. Concierge Medicine Market to Reach $13.3 Billion by 2030.” Business Wire, ResearchAndMarkets.com, 17 Aug. 2022, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20220817005601/en/U.S.-Concierge-Medicine-Market-to-Reach-13.3-Billion-by-2030—ResearchAndMarkets.com.

“Understanding Direct Primary Care.” Direct Primary Care Alliance, The DPC Alliance, https://dpcalliance.org/DPCU-Understanding-DPC.

“What Is Direct Primary Care?” Direct Primary Care Coalition, Direct Primary Care Coalition, http://www.dpcare.org/.